When traffic engineers plan the roads that eventually will accommodate traffic in new developments like this, the plans usually involve intersections with stop signs or signal lights. But the barren site of a future intersection might be an opportunity to consider another option for traffic management, the modern roundabout. These have been built by the tens of thousands worldwide. The main benefits have been to improve traffic flow and reduce injury crashes by as much as 75 percent compared with intersections controlled by stop lights or signs (see Status Report, May 13, 2000; on the web at www.iihs.org). But only about 1,000 roundabouts have been built in the United States.

“Transportation engineers, like everybody else, generally go with what they’re used to, and what they’re used to on U.S. roads is constructing standard four-way intersections equipped with stop signs or signal lights. Doing this means missing the benefits of roundabouts, so we’d like to encourage officials to consider roundabouts earlier and more often in the roadway planning process,” says Richard Retting, the Institute’s senior transportation engineer and author of two new studies that suggest how to overcome traditional impediments to building roundabouts.

One impediment is logistical: It can be costly and disruptive to tear up an existing intersection and replace it with a roundabout. The easiest way around this is to construct the roundabout to begin with, before an intersection with a traffic light or stop sign is installed. Another roundabout opportunity is when an intersection with a signal light is scheduled for major modification.

Institute researchers studied 10 intersections where roundabouts could have been constructed but weren’t. Instead local officials either outfitted the new intersections with traffic signals or retained the signal lights at intersections that were undergoing major modifications. The researchers measured traffic volumes, monitored the number of crashes that occurred, and estimated vehicle delays and fuel consumption at the intersections with the signals. Results were compared with estimates of what could have been expected with roundabouts instead.

A key finding is that vehicle delays at the 10 intersections would have been reduced by 62-74 percent, saving 325,000 hours of motorists’ time annually. Fuel consumption would have gone down by about 235,000 gallons per year, and there would have been commensurate reductions in vehicle emissions.

The safety benefits also are considerable. Previous research indicates that roundabouts reduce crashes by 37 percent overall - injury crashes by 75 percent - compared with intersections that have signals. Applying these risk reductions to 5 of the 10 intersections for which crash data were available, researchers estimated there would have been 62 fewer crashes over 5 years. There would have been 41 fewer injury crashes.

“If only 10 percent of the 250,000 intersections with signals in the United States were modified as roundabouts, the national safety and fuel saving benefits would be enormous,” Retting points out, “and you can reap these benefits without as many logistical challenges if you ‘think roundabout’ from the very beginning of a roadway project, for example when new housing or shopping developments create the need for roadway construction. Then it can be less expensive to construct a roundabout than to install traffic lights. Plus the developers may be required to fund the roundabout construction as a condition of zoning approval.

Initial opinion may be an impediment: Study after study, including the Institute’s most recent one in northern Virginia, indicates the benefits of roundabouts in reducing both crashes and traffic congestion. Yet roundabouts frequently run into opposition, especially before they’re constructed.

Institute researchers conducted telephone surveys of residents in three communities in New Hampshire, New York, and Washington State where intersections with stop signs or traffic lights were being replaced with roundabouts in 2004. The opinion surveys were conducted before the roundabouts were built and twice more, about six weeks after construction and then about a year later.

Fifty-four percent of the survey participants initially said they opposed roundabouts. One-third said they were strongly opposed. These proportions changed considerably right after construction, as motorists began getting used to the roundabouts. Then only 36 percent said they were opposed, and the proportion in favor increased from 36 to 50 percent.

“It might not sound like much of a victory to find out that half of the respondents expressed their approval for roundabouts. But the first follow-up surveys were conducted soon after motorists began navigating this new form of traffic control. Roundabouts weren’t yet routine,” Retting explains. Opinion surveys conducted more recently show growing approval. More respondents now say they like the roundabouts, while fewer say they disapprove.

Previous before-and-after surveys have revealed similar turnarounds in public opinion (see Status Report, July 28, 2001; on the web at www.iihs.org). This is because many motorists find out, through their own experience, that vehicles generally flow more smoothly through roundabouts than through intersections controlled by traffic signals. Delays are reduced. In many cases there’s no need to stop at a roundabout, just slow down.

Message for transportation officials: “What these two studies teach us is simple. Just build them. Go ahead and construct a roundabout where it’s appropriate, and do it, if possible, when a roadway is first engineered,” Retting advises. Especially in suburban areas where population growth and housing development are escalating and new roads are planned, officials would do well to consider roundabouts.

“Don’t let initial opposition get in the way,” Retting adds. “Many U.S. motorists aren’t familiar with roundabouts yet, so they’re wary of them. But once the roundabouts are built, the traffic flow and safety benefits turn people around, even people who weren’t enthusiastic from the get-go.” For a copy of “Continued reliance on traffic signals: a case study in missed opportunities to improve traffic flow and safety at urban intersections” by C. Bergh et. al and “Traffic flow and public opinion: newly installed roundabouts in New Hampshire, New York, and Washington” by R.A. Retting et al., write: Publications, Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, 1005 North Glebe Road, Arlington VA 22201, or email publications@ iihs.org.

Vail, Colorado: Town Without Signal Lights

Before the first roundabout was constructed in Vail, Colorado, ski season traffic was leaving visitors and local residents alike wanting to ditch their cars and just ski into town. Now traffic at every exit from an interstate highway entering Vail is governed by a roundabout. The result is that traffic backups have largely disappeared.

But the process wasn’t easy. The first proposals for roundabouts were resisted. Warren Miller, a local filmmaker, protested in the newspaper for six months. Still two roundabouts were built in 1995, and the opposition diminished as motorists got used to the new traffic patterns and noticed that vehicles were moving more smoothly. The newspaper published letters from Miller, who admitted he had been wrong. With public support, two more roundabouts opened in 1997. Now Vail is known as a town without signal lights.

Besides enduring fewer backups, motorists benefit in terms of safety. Greg Hall, director of public works and transportation, says crashes were reduced by about 20 percent from 3 years before the first roundabout to 3 years after. Injury crashes have gone down 85 percent. And despite initial concerns that bicyclists and others wouldn’t adapt to the roundabouts, there has been only 1 crash involving a bicycle in the 10 years since Vail opened its first roundabout.

Florida Community Gets It Right

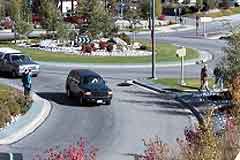

When the first roundabout (above) was constructed in Clearwater, Florida, the community’s traffic operations manager wasn’t a fan. “I’m an old signals and sign man. I never would have believed this would have worked, but it has convinced me that roundabouts do a remarkable job of accommodating all different kinds of users including cars, pedestrians, and bicycles,” says Paul Bertels. He recalls that the multiple signal lights that had controlled traffic at this location regularly brought vehicles to a halt and caused massive backups, but now the traffic keeps moving.

Bertels wasn’t the only skeptic when this roundabout opened in December 1999. Opposition began before construction and continued for a while afterward. But once engineers tweaked the design and motorists got used to the new traffic pattern, the complaints abated. In fact, Clearwater residents came to like the first roundabout so much that they requested another (below). They even collected $3,000 toward its construction and then held a party to celebrate when it opened (right).

Since then 3 more roundabouts have been constructed in Clearwater, and 7 more are being designed. All 10 of them were proposed by local residents.