Hard core drinking drivers have drawn extra attention in recent years as policymakers try to renew progress against alcohol-impaired driving and the deaths and injuries it causes. But the hard-core group isn't the whole DWI problem or even the biggest part, so it doesn't make sense to focus too narrowly on this group. The result is to overlook a lot of other impaired drivers who escape the definition of hard core.

|

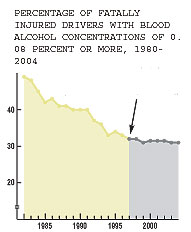

| This is when progress against alcohol impaired driving stalled, prompting a policy shift to focus on the hard core. |

'We've all seen headlines about crashes of impaired drivers with multiple prior offenses. These are problem drivers, but they're a smaller part of a bigger problem. Focusing on them ignores the more numerous impaired drivers who never have been arrested,' says Anne McCartt, Institute vice president for research and an author of a new report.

Hard core is difficult to identify: The Traffic Injury Research Foundation of Canada introduced this concept in the early 1990s to define people who resist deterrence efforts, repeatedly driving after drinking a lot. The hard core usually is defined as drivers with more than one traffic offense involving alcohol or drivers with blood alcohol concentrations (BACs) of 0.15 percent or more.

'Chronic offenders fit an intuitive idea of what the hard core is, but these drivers don't account for many crashes,' McCartt says. Among drivers with BACs of 0.15 to 0.19 percent who are killed in crashes, about 1 in 10 has a prior DWI conviction within the past 3 years. The proportion is slightly higher (12 percent) among fatally injured drivers with BACs of 0.20 to 0.24 percent. Even among drivers with extremely high BACs (0.25 percent or more), 16 percent of those killed in crashes have prior convictions on their records.

Recordkeeping on DWI offenses varies from state to state. Periods for counting prior offenses vary, and some drivers succeed in getting offenses removed from their records by, for example, completing alcohol education. The result is that repeat offender rates vary widely from state to state, and many hard-core offenders go unidentified.

Because repeaters are so difficult to identify, some people resort to using a BAC threshold of 0.15 percent to define the hard core. But this doesn't ensure identification, either, because the only motorists for whom BACs are reliably known are those killed in crashes or stopped and tested at the time of alcohol offenses. Even then BACs are known only at the time of the specific offenses. It isn't known whether an offense was an aberration, a sometime occurrence, or a frequent behavior indicating a hard-core problem. There's evidence that many drivers with BACs of 0.15 percent or more drink this much on occasion but not routinely. A study of drivers with such BACs found that fewer than half were chronically heavy drinking drivers.

'Although 0.15 percent BAC hasn't turned out to be a very useful indicator of the hard core, the distinction doesn't matter for enforcement purposes,' McCartt points out. 'As a group, drivers with very high BACs respond about the same as drivers with lower but still impairing BACs to DWI enforcement strategies.'

Progress for a while and then a stall: If hard-core drinking drivers are so difficult to define and identify, why is this group a focus of DWI policies and programs? The answer involves trends in alcohol-impaired driving over the years and, in particular, efforts in recent years to revive the progress that was made during the 1980s and 1990s.

In country after country, including the United States, sharp declines in crash deaths involving alcohol-impaired drivers began to be recorded in the early 1980s. In 1995 the Institute still was reporting that 'alcohol involvement in fatal crashes is on the decrease' (see Status Report, Aug. 12, 1995). Continuing well into the 1990s, this progress was widely attributed to effective DWI laws, heightened enforcement, and increased public attention to the problem spurred by groups like MADD.

Among the best programs were sobriety checkpoints, characterized as 'probably the most effective deterrence strategy we can apply' (see Status Report, April 2, 2005; on the web at iihs.org). Other effective measures included raising the minimum age for purchasing alcohol, reducing to zero the allowable BAC for young drivers (see p.5), and enacting laws making it quicker and easier to suspend or revoke the licenses of DWI offenders.

As these and other laws took effect, proportions of fatally injured drivers with BACs of 0.08 percent or more declined to about one third in 1997 from about half in 1982. The declines were similar among drivers with BACs just above 0.08 percent and drivers with BACs of 0.25 percent or more.

Then the progress stalled. The ensuing search for new ways to reduce the alcohol impaired driving problem led policymakers to focus on the hard core — that is, on the drivers who presumably are the most resistant to obeying DWI laws.

New laws began targeting this hard-core group. Under the 1998 Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century, the federal government withheld highway construction funds from states that didn't enact provisions to impound the vehicles of second DWI offenders or make them use ignition interlocks. License suspensions and jail terms were extended. A subsequent federal law initiated another round of sanctions against drivers identified with BACs of 0.15 percent or more. Most states have enacted such laws.

Some of the provisions have been effective. Interlocks, which indicate the alcohol in drivers' blood and keep people with specified BACs from starting their vehicles, reduce repeat offenses (see Status Report, Jan. 15, 2000; on the web at iihs.org). Yet the overall result of focusing on the hard core hasn't been impressive. Since 1997 about 31-33 percent of fatally injured drivers have had illegal BACs (0.08 percent or more). Proportions with higher BACs (0.15 percent or more) also have held steady.

This doesn't mean drivers with very high BACs aren't problems. They are, whether or not they're defined as part of a hard-core group. More than 60 percent of drinking drivers killed in crashes have BACs of 0.15 percent or more.

'The problem is targeting these drivers at the expense of programs aimed at other drivers with BACs high enough to elevate crash risk. Why let them off the hook? Why exclude any driver with a BAC high enough to impair driving? Target them all,' McCartt says.

Target every offender: General deterrence programs like sobriety checkpoints target all drivers with laws and enforcement to convince them they'll pay a high price if they become impaired by alcohol and then get behind the wheel. Specific deterrence involves penalties especially for repeat offenders and drivers with very high BACs who are identified through general deterrence programs. Penalties for these drivers may include incarceration, vehicle impoundment, ignition interlocks, or other sanctions. While evaluations indicate that some of these strategies can reduce recidivism, they aren't as important as general deterrence because they don't target as many potential offenders.

'It's a matter of the probabilities,' McCartt points out. 'An estimated 90 million vehicle trips per year involve alcohol-impaired drivers, but only about 1.5 million of these end in driver arrest. Given such low arrest likelihood, the first priority needsto be to raise the probability that all impaired people, including the hard core, will be deterred from driving or, if they do drive, will be arrested for the offense.'

A broader approach is to take steps to reduce overall alcohol consumption. This recognizes that many of society's problems, including but not limited to deaths and injuries in crashes involving impaired drivers, result from alcohol consumption. But there are big challenges. One is that trying to reduce intake goes against vested interests including the corporations that produce and distribute alcoholic beverages. Another challenge involves public acceptance. Surveys show a clear preference for punishing DWI offenders over curbing everyone's consumption.

A future approach might involve equipping every vehicle with technology that measures a driver's BAC and prevents driving if the BAC is high. Such technologies, which will have to measure BACs more quickly and unobtrusively than breath devices, are being developed (see Status Report, April 2, 2005; on the web at iihs.org). The potential is to keep all impaired drivers from starting their vehicles.

'Whatever approaches we develop or revive from the 1980s, it will be important to recognize that punishing the hard core won't be enough to make a big difference — and it will be counterproductive to the extent that it draws attention away from the occasional heavy drinkers and the numerous impaired drivers with lower BACs and no priors,' McCartt concludes. 'Targeting the broader group with general deterrence will net the hard core too.'

For a copy of 'Hard-core drinking drivers and other contributors to the alcohol-impaired driving problem: need for a more comprehensive approach' by A. Williams et al., write: Publications, Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, 1005 North Glebe Road, Arlington, VA 22201, or email publications@iihs.org.